This year Russia will hold nation-wide legislative elections and the talk of the town, for months, have been whether the Kremlin’s expectation is for United Russia, which presently holds 343 of 450 seats – a comfortable constitutional supermajority – in the Duma, to win a constitutional supermajority again and whether this is a realistic expectation at all. It is, as I show below. It is also risky.

It is fair to ask the question, because the situation is very different from 2016. United Russia was not highly popular five years ago, either, but it was in a better shape than it is now. In August 2016 the independent Levada Center found that the electoral rating of the party (the percentage of Russian citizens who planned to participate in the election and planned to vote for United Russia) was at 50 percent. Now it is 43. Furthermore, while Russia was going through an economic slowdown in 2016 that affected the income of voters, this was a relatively new phenomenon; it is fair to assume that five years later, with real incomes still falling, people are in a worse mood. The “Crimean consensus”, a special rally-around-the-flag effect that ensured sky-high ratings for Vladimir Putin following 2014, has since worn off as Putin’s popularity and especially his trust rating took a hit after the government’s pension reform in 2018. United Russia’s rating had of course not always followed Putin’s popularity closely, but this means that there is one fewer cushion for the party to fall back on.

In August I argued that elections, however rigged, are still an important source of legitimacy for the Kremlin, but winning them for United Russia required an increasing amount of tinkering with the electoral system and rigging. And this was important because “[e]ven if many voters have become cynical about elections in Putin’s Russia, this legitimacy deficit matters. It is easier to put up with a farcically hollowed-out election as long as the result largely reflects actual attitudes or as long as it is broadly understood that the election does not matter anyway. But the gap between official results and people’s attitudes has been widening. The fact that an ever-increasing toolbox of tricks and workarounds is necessary to produce the same result is proof of this. And in certain cases, people seem to have realized that elections do matter.”

This was one of the big stories of 2020. So what will happen in 2021? How bad are the prospects of United Russia? I looked at some numbers.

Trends and outliers

Russia held a total of 40 regional legislative elections in 2018-20: in Moscow, in 37 regions and in the annexed territories of Crimea and Sevastopol, which I will consider regions for the purposes of this inquiry, since their residents voted in the 2016 Duma election. Without Moscow, these regions collectively represent 37.1 percent of Russia’s population. Apart from Moscow where elections to the Municipal Council take place in a majoritarian system, every other legislative election had a proportional track, which allows a straightforward comparison between United Russia’s results in the 2016 Duma election and these regional legislative elections.

Note that due to the differences between the nature of a regional and a national election the comparison must of course come with caveats. One is that the figures running on regional United Russia tickets tend to be players with local interests – e.g. local businessmen – who therefore have a strong personal incentive in turning out the vote in their favour, even if the party does not receive adequate funds from the federal center. However, United Russia is widely regarded by voters, in the regions as well as on the national level, as “the party of power”, which makes the comparison easier. Another caveat is that interest and thus turnout is usually lower in regional elections – through just like in national elections, there is a wide spread from apathetic Far Eastern regions to the North Caucasus where a combination of clan structures, coercion and rigging usually ensure an exceptionally high turnout. Outside these bastions low turnout actually benefits United Russia: one of the strategies employed by the party in the past years has been suppressing turnout in regions where it is in trouble and using its administrative leverage to turn out the United Russia vote or inflate the party’s results in other ways. Alexander Kynev, a political analyst recently warned that a higher turnout in national legislative elections could reduce United Russia’s proportional result by as much as 5-6 percentage points relative to the latest regional elections, which would neatly place it just under the 43 percent that Levada measured.

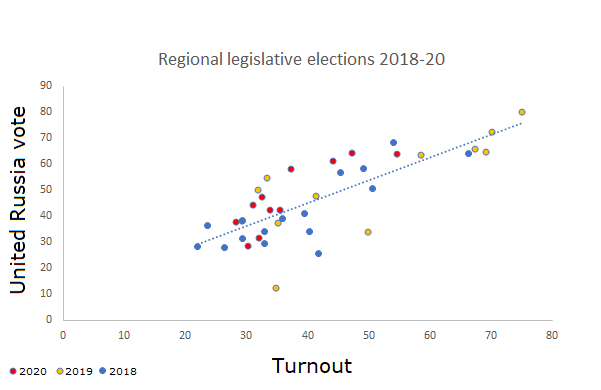

The first chart (using data from Russia’s regional electoral commissions) shows that there indeed seems to be a correlation between turnout and United Russia vote in regional election, but this is mostly driven by a couple of outliers: four republics – Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, Tuva and Tatarstan – which traditionally fall into the category of the ethnic regions with high turnout and high United Russia vote – and a couple of regions – Magadan, Voronezh, the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District, etc. – that registered high support for United Russia in 2020, after, ostensibly due to the pandemic, the Duma made it possible to hold elections over three days and restricted the activities of election observers. Other outliers in this direction include Crimea (in 2019), the Republic of Kalmykia in 2018 and two non-ethnic regions with their own specificities: Belgorod with its viceroy-esque governor, Yevgeny Savchenko who had been leading the region since 1993 (and resigned shortly after this election) and Bryansk, a region in the strategic position of bordering both Belarus and Ukraine where increased smuggling has greatly benefited local crime gangs and entrepreneurs in recent years.

On the other side you would find the Khabarovsk Territory – mediocre turnout, miserable United Russia result (12.51 percent) – where the party of government was all but wiped out in 2019, one year after the surprise election of the since-arrested Sergey Furgal; and Khakassia, which, like Khabarovsk, voted a United Russia governor out of office in 2018 and held a legislative election in the same year.

However, indeed because of the specificities of these regions, this chart in itself does not tell us much about United Russia’s position changed overall; so I compared the official results of these regional elections to United Russia’s official Duma election result in these regions in 2016.

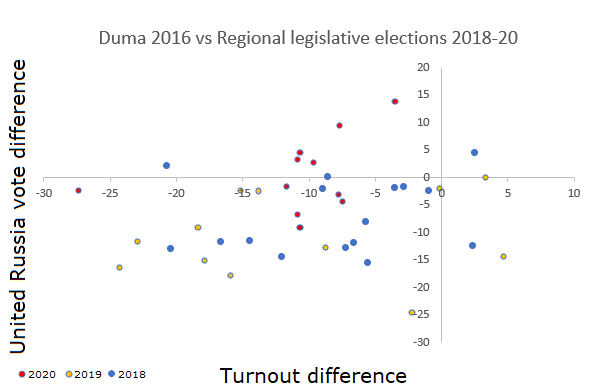

Turnout in regional elections was lower almost everywhere, but this is expected. However the chart also shows the serious hit that United Russia took in 2018 and 2019. Again, there is a contrast with 2020 when, defying the previous trend, United Russia managed to improve its results relative to 2016 in a curiously large number of regions (none of which was a traditionally “high-turnout, high-United Russia” region, but none of which experienced major political upheaval in the preceding year, either). This could of course partly be the result of voters supporting the ruling party during a major health crisis, but there is scant evidence of that kind of rally-around-the-flag effect in Russia and it’s difficult not to see, in these results, the effect of three-day voting and the increased opportunities of rigging.

What really worries the Kremlin are the regions where turnout in regional elections did not drop significantly – or even increased – while United Russia’s vote share dropped significantly, because this is where, we can assume, previously apolitical people were mobilised to vote against the ruling party: aside from Khakassia, the Khabarovsk Territory (and perhaps the Vladimir Region, which also elected an opposition governor in 2018) the far eastern Altai Republic fits this description. The region has had a nasty COVID-19 outbreak this year and went through significant political turbulence as the regional legislature rose up against a Kremlin-appointed governor, but due to its small size, it probably worries the Kremlin less than other, more populated regions, such as Novosibirsk, where а low turnout in the 2020 regional election – under 30 percent – masked an increasingly vibrant and potent opposition.

Tough choices ahead

The two partial conclusions are that even if United Russia’s regional results are normally diminished by higher turnout in the Duma election, as of 2020 there is also a new baseline of how much this result can be changed through administrative means, pressure or rigging, provided the command lines work flawlessly or interests align; and that while at this point there is only a small number of regions where previously inactive voters have been mobilised against the ruling party, there is ample room for this to happen in other regions and this possibility worries the Kremlin.

It is easy to see why, if we zoom out again and look at United Russia’s 2016 results. The party officially took 54 percent of the proportional vote, resulting in 140 (of 225) mandates. While this result was likely inflated somewhat, it is not highly disproportionate, knowing what we know about United Russia’s electoral rating in August 2016. Furthermore, this track of the electoral system does not distort the result excessively. United Russia had to get roughly 203,700 votes for a mandate, slightly less than A Just Russia (SR), slightly more than the Communist Party (KPRF) and about the same as the Liberal Democratic Party (LDPR). In the majoritarian elections that decided the other half of the Duma’s deputies, however, United Russia won 203 of 225 districts, thanks to the first-past-the-post system, which rewards incumbents facing a divided opposition. With a vote share lower than what it registered in the proportional vote, United Russia took 90 percent of single-mandate districts. This is what the party’s constitutional majority hinges on.

In 88 of these districts, United Russia won by taking less than 45 percent of the vote and in 11 districts the vote share of the winning United Russia candidate was less than one third of the total vote. As long as the opposition vote is divided, it is relatively easy to hold on to these seats even if the party’s overall rating is lower. As soon as opposition voters – or previously inactive voters – rally behind one candidate, however, the system can easily become a double-edged sword (with an even more immediate effect than in gubernatorial elections where it first simply forced a second round, allowing wheeling and dealing). Alexey Navalny’s “smart voting” initiative was going to attack exactly this weakness. And it was working increasingly well.

United Russia simply cannot afford to lose these seats. It is difficult to estimate how many votes will officially be awarded to the party, given uncertainties about rigging and the possibility of new parties entering the Duma. But if we are to make an educated guess that takes into consideration both the new “manipulation baseline” seen in 2020 (keep in mind that unlike last year’s constitutional referendum high turnout is not a goal in Duma elections) and the apparent acknowledgement that it is going to be necessary to shake up the party system just a little, we can speculate that with United Russia’s present electoral rating it may count on 110-115 proportional mandates. It would then need to win 185-190 single-mandate districts for a constitutional supermajority. This is 13-18 less than in 2016: dangerously close to the number of those very weak victories in 2016.

Without smart voting a constitutional supermajority is, if not guaranteed, but perfectly possible with the party’s present electoral rating, especially if a handful of new parties are also running in key races in problematic districts (where they are being actively built up). With smart voting, it is very questionable. Losing all 88 districts, in which it won with less than 45 percent of the vote in 2016 – admittedly an extreme scenario even if smart voting works – may even jeopardize United Russia’s majority in the Duma, let alone its supermajority. Even if only the “systemic” opposition gets seats, their increased bargaining power would be uncomfortable for the Kremlin in a period when it is increasingly focusing on maintaining stability at all costs.

This is why the Kremlin is doing what it can to block “smart voting”, keep Navalny abroad – the second-best thing from Putin’s perspective after the botched poisoning – and make it all but impossible for campaigners in Russia to rally voters behind strong non-incumbents. The caveat, of course, is the Kremlin has to tread a fine line: this strategy will hardly solve the legitimacy crisis. If anything, it may make it worse.