The ruling United Russia’s congress in November seemed to confirm that Russia’s leaders intend to rely on the party in the early 2020s as Vladimir Putin’s fourth presidential term draws to an end. This was significant because recent years have seen constant speculations about the coming demise of the increasingly unpopular ruling party or a “party system reform” by political technologists in the Kremlin. Now the talk is about a reform of the electoral system to make United Russia’s position more stable. But in this case too the status quo is the safest bet. Here is why.

Electoral reform is a perennial issue in Russian politics. Until the 2003 legislative election deputies had been elected in a mixed system that used both single-mandate districts (SMDs) and a proportional branch for party lists. Then two elections were held in a fully proportional system with a parliamentary threshold raised to 7% – in 2007 and in 2011 – before the country returned to a mixed system for the 2016 election with the previous threshold of 5%. And as Russia is nearing 2021 when the next State Duma will be elected – the legislature that will be in power when Vladimir Putin’s fourth presidential term ends in 2024 – rumours abound about the Presidential Administration contemplating changing the system again.

According to these rumours an idea floated by Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and the nominal head of the United Russia party is to “divide the country into 225 SMDs” (this is already the case in the present mixed system, although redrawing district borders could certainly shake things up) and do away with the proportional branch. In such a system, so the thinking goes, United Russia would be able to get 180 to 200 mandates, an overwhelming majority. Presently, United Russia holds 343 of the Duma’s 450 seats, a constitutional supermajority. This includes 203 out of 225 single-mandate seats. In a somewhat more modest projection at United Russia’s congress in November party officials suggested that the goal for the party was to preserve its supermajority, that is, to win at least 301 mandates out of 450 in 2021. Given how restrictive the rules governing parliamentary groups are in the State Duma (which in any case can always be tightened further), this would guarantee a solid majority in 2024. More importantly, Putin apparently wants United Russia – rather than pro-Putin “independents” or another party with a fresh brand – to hold this stable majority.

In a proportional electoral system winning another supermajority would be close to impossible without significant rigging. United Russia’s popularity has taken a nosedive in recent years. According to the independent Levada Center, the party was supported by a mere 28 percent of Russians in July 2019, down from 39 percent in June 2017. This would translate into up to 44 percent of the vote in an election, about as bad as (or worse than) in the scandal-ridden 2011 election when the authorities had to commit significant and blatant falsifications in order to grant the party a simple majority. With the mixed system that Russia presently has, it will be a much easier task. In 2016 United Russia officially won 55 percent of the vote and 76 percent of seats. Even if the party had only scored 40 percent of the votes cast for party lists, with a good strategy in single-mandate districts it probably would have been able to take a two-thirds supermajority.

The keyword (or rather, key phrase) is “first-past-the-post”. In the 225 SMDs that gave United Russia the mandates it needed for a supermajority, the party’s candidates did not have to win the majority of the vote: a plurality was enough, and this is relatively easy to guarantee if the opposition is sufficiently fragmented. To be on the safe side, you can always set money aside for “spoiler candidates” who will take votes away from your opponents. Indeed, as a former political handler in one of Russia’s regions disclosed to Meduza’s Andrei Pertsev recently, about 10 percent of campaign budgets go on “dark money” services, one of which is spoiler candidates. Other authoritarian leaders have used the same tactic with significant success. The party of Ukraine’s former president Viktor Yanukovich managed to increase its mandates in the Rada significantly when Ukraine used a similar system in the 2012 legislative election, even as the party’s overall popularity fell. The 2018 parliamentary election in Hungary returned Viktor Orban’s Fidesz to a constitutional supermajority, even though the party’s list was supported by less than 50 percent of voters.

Why then, supposing that the authorities possess the financial and administrative means to keep the opposition fragmented and to keep unwanted candidates from running, would it not make sense for Russia’s government to switch to an entirely majoritarian system with 225 (or 450) single-mandate districts and keep winning supermajorities as long as they can keep the opposition divided?

Demotivated

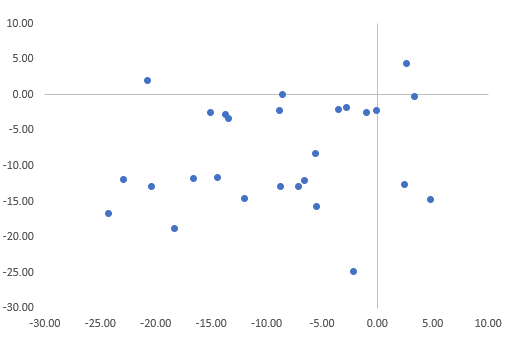

Preserving United Russia’s position in various elections over the past eight years required more than administrative pressure and spoiler candidates. It depended, to a large extent on demotivating voters. The graph below shows the differences in turnout (on the horizontal axis) and United Russia vote share (on the vertical axis) in Russia’s 83 regions between 2011 and 2016, in percentage points (due to large-scale rigging the data are to be taken with reservations, but they do provide a good proxy to understand the phenomenon of electoral apathy).

In 2016 turnout decreased in all but five regions (Tyumen Oblast, Tuva, Karachay-Cherkessia, Dagestan, Kemerovo Oblast), in most regions by 5-20 percentage points. This, however, did not typically lead to a fall in votes for United Russia. Indeed, in most regions it was opposition voters who were demotivated. In regions where the ruling party lost votes, the loss was typically minor (0-5 percentage points). Outliers were either sparsely populated (e.g. the Komi Republic) or regions where United Russia still registered a large majority of votes (e.g. Ingushetia). The two significant opposition gains were registered in Moscow (where turnout was down by 26.5 points and United Russia by 8.84) and, to some extent, in the populous Chelyabinsk Oblast (-15.13 and -11.21).

The fact that the 2016 legislative election was quiet and dull did not surprise anyone. The collective political delirium that followed the annexation of Crimea was still in near-full swing. With opposition movements temporarily marginalized and “systemic” opposition parties less distinguishable from United Russia than ever in the “Crimean consensus”, it was an easy game to win, even as GDP and real wages were falling.

Since 2018, however, a different picture has emerged. Putin’s re-election in 2018 required widespread mobilization to give legitimacy to the president as the country was sobering up in a hangover following four years of damaging geopolitical posturing and domestic mismanagement. Officially, more than 76 percent of voters supported Putin with a turnout of 67.5 percent, although there is reason to suggest that the numbers were doctored. The real shock came when over the summer, following a series of local protests and an unpopular pension reform, Putin’s ratings started falling rapidly. Four surprising upsets in gubernatorial elections in September 2018 showed that old methods of engineering electoral campaigns – e.g. having Putin endorse a candidate – did not work flawlessly any more.

It’s time for another telling graph. This one shows Russia’s 27 regions, which held legislative elections in 2018 or in 2019. The horizontal axis shows the difference in turnout between 2018/19 and in the 2016 Duma election; the vertical axis shows the difference in United Russia’s share of the vote. It goes without saying that there is always going to be a natural difference between the turnout in a regional and in a national election, therefore the story here is not one of falling turnout. What the graph shows is that in 2018/19 those who did turn out to vote in regional legislative elections disproportionately voted against United Russia. In 13 regions the ruling party’s vote share was more than 10 percentage points below its 2016 result in the same region and in 8 regions this happened with a comparatively high turnout. In the Khabarovsk Krai, one of the regions that in 2018 elected an opposition governor, United Russia was essentially wiped out even as turnout remained close to the 2016 Duma vote. In Moscow where this year’s election to the Municipal Council were preceded by mass protests, the only way the authorities could limit the damage was scaring people into staying home. Only in three regions out of 27 – the Sakha Republic, Bashkortostan and the Yaroslavl Oblast – was the ruling party able to reproduce the same result as in 2016.

The road often traveled

This matters for three reasons. First is that seemingly demotivation, which had benefited United Russia in the past, stopped working. This is not entirely due to falling real wages or the unpopularity of the pension reform. The expansion of Alexei Navalny’s network in the provinces, which reinvigorated public discourse – which the authorities targeted with various legal means this year – helped a lot, as did nation-wide protests against the pension reform organized, in part, by the Communist Party. Voters also increasingly take a different view on elections. As a crisis of political responsibility developed in Russia over the last decade, the government’s role in decision-making has more or less shrunk to merely implementing decisions. Decisions are increasingly prepared by experts trusted by the president. They hold various positions from the Central Bank to the Audit Chamber. Decisions on their suggestions are often taken by the Security Council, which officially only has an advisory role, and receive a final, political nod from the Presidential Administration, an unelected body. Governors, most of whom are, even if they are officially elected, appointed from Moscow (often together with their supposed “opposition”) have seen their political authority decrease in recent years, save for a few who hold real sway. One of the most often heard criticism of United Russia, even inside the party, is that in many regions it simply lost the ability to communicate with and mobilize voters and offer them a vision. Voters are thus increasingly likely to call the president, the only elected public official with visible and tangible political authority, responsible for local failures from waste collection in the Moscow region to disputed urban development projects in Yekaterinburg. In such circumstances elections may become opportunities for the electorate to send a message to the man with real authority. Some already have. Navalny’s smart voting – supporting the “systemic” opposition candidate with the best chances to win – has its limits but it is probably in elections where winners take all that it has the best chance to make a difference.

Second is the role regional leaders are playing (and expected to play) in the successful management of elections. United Russia is far from being a monolithic party either at the federal or at the regional level. Its performance and embeddedness in local institutions vary between tightly controlled North Caucasian republics where the party usually scores over 70 percent of the vote, wealthy regions with their own strongmen, such as Tatarstan or Bashkortostan that can be trusted to ensure a strong outcome, and “problematic” regions, either with a vivid civil society, such as Moscow, or a population that feels removed from Moscow where decisions are taken. It’s no surprise that United Russia wants local leaders to be more tightly engaged with the party. Putin criticized candidates in Moscow who ran as independent in September, as if they were running away from a toxic brand. Plans emerged to require governors to head regional branches of the party. Campaign financing is allegedly changing, putting more emphasis on local actors over transfers from Moscow.

Finally, there was seemingly a strategic decision in the ruling elite that United Russia will be preserved as the ruling party. According to Tatiana Stanovaya, an eminent analyst of Russia’s political elite Putin considers the party “crucial” and his risk aversion cautions him against changing the playing field even as the party’s brand is in trouble. In July this year I argued that United Russia, while not quite a “party of power”, is still an important political tool to coordinate the work of political leaders and public servants and that its material wealth and political power made it too big to fail. Many have high stakes in the party, from its nominal leader, Dmitry Medvedev to Vyacheslav Volodin, the speaker of the State Duma who used to be its actual leader in all but name until recently, and Andrei Turchak, the general secretary of the party (and the son of one of Putin’s judo partners) who was probably appointed to contain Volodin’s influence.

And perhaps as long as United Russia is around – either because of Putin’s risk aversion or because it is too big to fail – there is simply no other choice but to keep sticking to it. In the past decade whenever the possibility of a “second ruling party” emerged (usually on anonymous Telegram channels or in discussions between Russia watchers with a rich fantasy), it was based on the assumption that Putin’s constituency is large enough to accommodate a second ruling party. The All-Russia People’s Front, a pro-Putin umbrella organization created in 2011 to shore up his support before his return to the presidency in 2012, was based on the same idea. Perhaps the decision about the leading role of United Russia is a tacit acknowledgement that this is not so: Putin’s shrinking constituency could not accommodate two parties that are different enough to stimulate interest. When voters increasingly make the president responsible for policy failures, it is difficult to build a compelling opposition party that is loyal to the same president.

Vyacheslav Volodin once famously said that “without Putin there is no Russia”. Nowadays the question seems to be whether there is Putin without United Russia.