On September 8-10 Russia holds regional gubernatorial or legislative elections in 33 of its 83 regions, including in Moscow. Apart from these votes, a number of municipal votes will be held across the country, and the occupying authorities will stage elections in four occupied regions of Ukraine. Below is a short overview of what is at stake in these elections and what to look out for.

In the occupied territories, the votes constitute a means for Moscow to show force and demonstrate that it is capable of implementing its political will in spite of a continuing Ukrainian counter-offensive. While officially several Russian parties are participating in these votes as well, fielding a motley crew of local officials and power brokers as candidates, they will take place under conditions of martial law and the results are likely to be mostly or completely falsified, similarly to those of the 2022 “referenda”.

Domestically, the votes have a different stake. Even under Putinism, elections have played an important legitimizing role in Russia, both by showing the support that the system can engineer in favor of desired political outcomes, and by testing the regime’s flexible coercive capacity against changing realities on the ground. As such, elections have always been approached with a mixture of repression and manipulation. Apart from more overt rigging, the toolbox included frequent changes to electoral legislation, administrative pressure on voters via officials and corporations, institutional control via electoral committees and tools such as the “municipal filter”, which prescribes gubernatorial candidates to obtain the support of a set number of deputies in municipal councils mostly controlled by United Russia.

One important change over the past years has been a growing reliance on repression instead of manipulation, which has taken place along with the strengthening of the vertical of power over regional governments.

What has changed?

To understand the direction, in which the system has been developing, we can compare this year’s election to the regional votes of 2018 (when many of the same regions last held similar votes); to those of 2019-2020 (when Alexey Navalny’s “Smart Voting” and grassroots activism resulted in opposition successes in cities); and to those of 2022, the first elections after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The comparison with 2018 is striking: that year the votes took place following the adoption of a highly unpopular pension reform, which many interpreted as Vladimir Putin reneging on assurances he had personally made earlier during his rule. The fact that this happened after several years of falling or stagnating real incomes and – in certain regions – a growing disconnect from Moscow, whose development budget ballooned after the 2011-12 protest wave, allowed dissatisfaction to evolve into various forms of protests. These included the more traditional sort of marches, often supported or organized by local Communist Party (KPRF) chapters, but also protest voting, which led to four surprising electoral upsets for United Russia in that year’s gubernatorial elections (along with setbacks in legislative and municipal votes). In 2018 the system’s vulnerability to the protest voting of a very diverse group of dissatisfied voters was laid bare in such a way that inspired years of strategic protest voting. This ultimately led to opposition triumphs in Moscow in 2019 and in Tomsk and Novosibirsk in 2020, making politics significantly more pluralistic in these cities.

For the Kremlin, the lesson derived from the 2018 votes was that experimenting with pluralism in the regions was not worth its benefits. In the years that followed, three of the four opposition victories of 2018 were invalidated or even punished. Direct mayoral elections in Novosibirsk and Tomsk were scrapped. In 2023, even political pluralism as a concept looks like a thing of the past, as the past two years have seen increased repression against grassroots opposition initiatives and campaigns, and several regions and cities changing their electoral rules in ways that typically benefit the ruling United Russia party. Six of the sixteen regions holding legislative elections this year have increased the number of mandates distributed in a majoritarian, first-past-the-post system that benefits the strongest party. Kalmykia, a poor region in Southern Russia, completely revamped its electoral system months before the vote. The Maritime Territory banned independent gubernatorial candidates.

The rolling out of online voting in an increasing number of regions, has been accompanied by reports of administrative pressure by officials and company managers, and its opaqueness further complicates election observation. As of early September, close to 7 percent of voters in the affected regions have signed up (though with significant variation between regions); given traditionally low turnout at regional elections, manipulating these votes could make a large difference. Nonetheless, online voting is not so much a kill switch that the authorities can simply push to negate actual electoral outcomes, but a novel way of practicing the same methods – ballot stuffing, administrative pressure – that have been observed in traditional “offline” voting in the past, just like multi-day voting, introduced in 2020. In 2021 online voting in Moscow – which runs a separate system – was key to overturning what looked like opposition successes in that year’s Duma elections.

In May this year, the State Duma further tightened electoral legislation, introducing restrictions on the participation of “foreign agents” – a label whose applicability has also been stretched repeatedly over the past years to allow the authorities to designate practically any critic if they so wish – media coverage and the access of independent observers, among other things. The changes also made it possible for the authorities to hold elections in the occupied territories under martial law. The Kremlin has also strengthened its control over electoral committees through United Russia and nominally independent personalities. A recent study of the renowned independent election observation group Golos found that United Russia controlled roughly 80 percent of electoral committees either by providing their chair or a sufficient number of deputy chairs. These committees, together with courts, disqualified a fourth of gubernatorial candidates, including all independent (non-party-affiliated) candidates.

Even without straight-out disqualification, most parties are playing it safe. Only 12 of them have gubernatorial candidates, most of them from United Russia, the Communist Party and the Liberal Democratic Party. The remaining two parliamentary parties, Fair Russia and New People, for various reasons did not field gubernatorial candidates in every region. United Russia, whose governors often ran as “independents” in the past to avoid open association with the party of power, this year required all of them to run as United Russia candidates – even Moscow mayor Sergey Sobyanin who has cultivated the image of a political force on his own. While lower-level elections are less tightly controlled, looking at the wider field, the dominance of the ruling party looks even starker. United Russia fielded more than 33,000 candidates, while the Communists and the Liberal Democrats have between 8,000 and 9,000 each.

This tightening of the political field has been years in the making, but, similarly to other fields, the war acted as an accelerator. The contrast with last year’s regional votes is not immediately obvious, but the nuance is as important as the stark contrast between the pluralist outbursts of 2018 and the suffocating atmosphere of 2023.

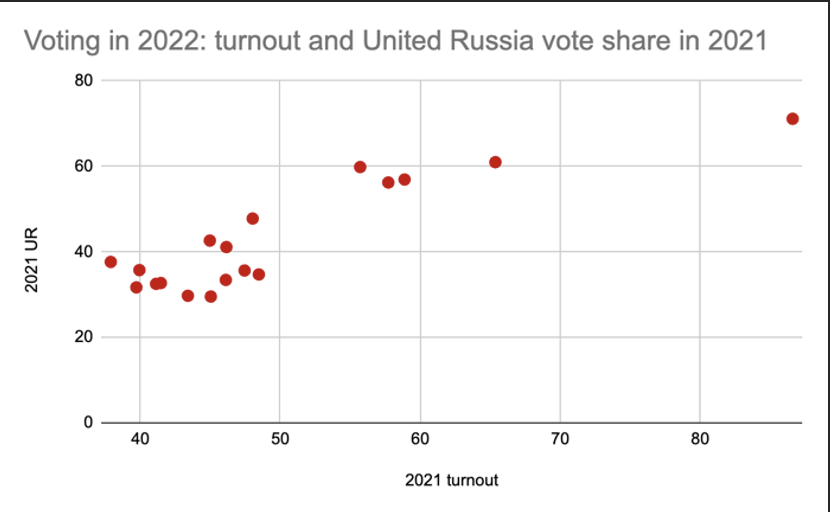

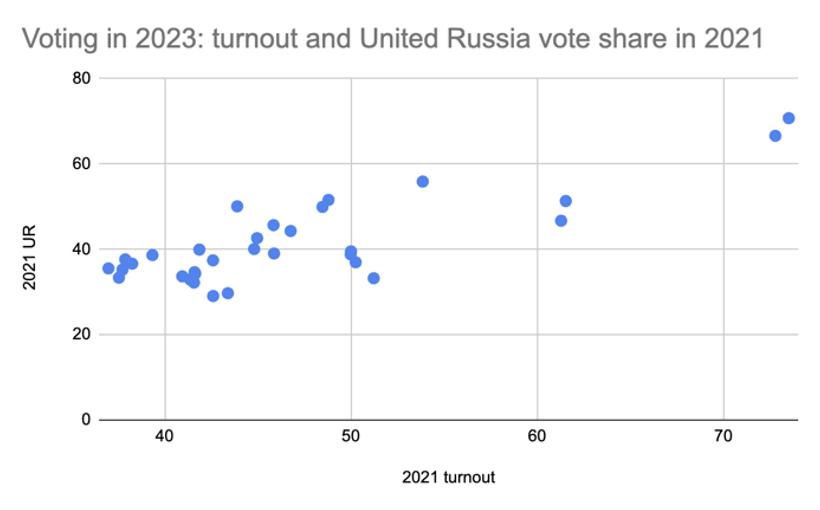

Comparing the 2021 Duma election voting patterns of the regions that voted last year with those voting this September – apart from the fact that roughly twice as many regions will hold elections this year – we see a very similar mix of more pluralistic regions and regions where the authorities are able to engineer a more sound majority for the ruling party.

Figures: 2021 Duma election voting patterns of regions holding regional gubernatorial or legislative elections in 2022 and 2023. Source: Central Electoral Committee of Russia

What is different this year is that Russian domestic politics has been forced on a new trajectory, which in 2022, a mere six months after the full-scale invasion, was not fully visible. Since then, however, hopes that the war will end in the near future have evaporated; Russia’s decoupling from Western finance and trade, while incomplete, is already forcing longer-term structural changes onto the country’s economy and domestic politics. Regional and municipal budgets and the officialdoms executing them are under increasing strain, as evidenced by a growing propensity of regions to take out loans from the budget, the Kremlin showing concern for municipal finances and even some mayors openly venting their frustration due to a lack of funds allocated from regional budgets. It appears that while most have come to accept that there is a new normal, many of the details are still in flux. A situation like this lends itself to conflicts.

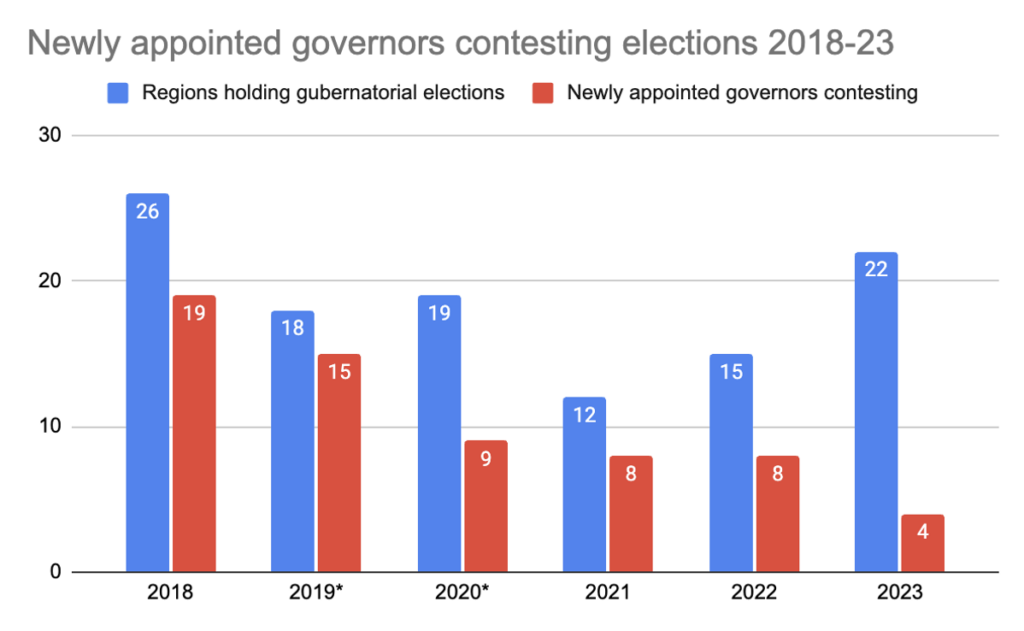

However, the Kremlin has tried to tread carefully. Following last September’s regional elections, Putin refrained from dismissing governors, and in the spring, when further replacements usually happen (leaving time for newly appointed governors to set up their modus operandi with local elites and officials), he dismissed only four: mostly unpopular figures and representatives of the systemic opposition.

Figure: Governors appointed between elections contesting gubernatorial elections in Russia; 2019 and 2020 figures do not include the occupied Crimea and Sevastopol; Source: Central Electoral Committee of Russia

In spite of a publicity campaign about integrating “war veterans” into domestic politics at the beginning of the year, very few were actually allowed to stand as candidates, mostly officials who served a couple of months in Ukraine for show. The second part of a public administration reform, which would eliminate thousands of free-standing municipalities and strengthen the power of governors over mayors, was postponed, presumably to avoid creating conflicts (even though several regions have started to eliminate local self-governance structures on their own). Indeed, where the Kremlin’s representatives did dare to upset understandings with local power brokers, these were typically opposition representatives. In Novosibirsk, the Kremlin-appointed governor, Andrey Travnikov – a non-native of the region – upset a power-sharing deal with the regional KPRF organization and its leader, Novosibirsk mayor Anatoly Lokot, scrapping direct mayoral elections. This has led to protests and petitions, but Lokot decided not to run personally against Travnikov (in the neighbouring Altai Territory, where the communists did field one of their strongest local politicians, Duma deputy Maria Prusakova, as a gubernatorial candidate, United Russia prevented her from running, using the municipal filter). In the Maritime Territory, the KPRF even raised the possibility of a boycott after their representatives were excluded from local electoral committees.

These local conflicts show the pressure points of regional governance, as do the topics that have dominated regional and local campaigns (apart from strictly local issues). While anti-war messaging remains taboo – candidates who try this, even in more pluralistic regions, risk disqualification if not criminal prosecution – the economic and social effects of the war are present in campaigns, from inflation and social measures benefiting war participants to prospective investments in defense plans and Russia’s Eastern pivot, or indeed a lack of funds as a consequence of the prioritization of the war. Even aside from these, the war has been present in the background. It appears that the fact that the Kremlin’s (now former) candidate for the governorship of Khakassia, Sergey Sokol presented himself as a war participant, did not do him any favors. There are similar stories from other regions: in Novosibirsk voters have initiated the resignation of a deputy who was appointed advisor to the head of the Russian-occupied Donetsk region and apparently neglected his district as a consequence.

What to watch out for?

- Khakassia’s election: Khakassia is the only region that had a genuinely competitive electoral campaign. Here communist governor Valentin Konovalov, the last winner of four 2018 electoral upsets still in office, was facing a challenge by Sergey Sokol, a Duma deputy and former war participant, considered to be an ally of Presidential Administration deputy head Sergey Kirienko. The region, with only a couple of hundreds of thousands of voters, saw a pretty eventful campaign, in which Konovalov tried to rally local elites around himself, presenting Sokol as an outsider. He successfully “poached” officials from United Russia, among them, notably Vladimir Stygashev, the long-time head of the regional parliament, and forced Sokol to participate in a series of televised debates. The conflict also affected the region’s electoral administration: Konovalov’s administration opted out of online voting (similarly to six other regions), but it could not prevent multi-day voting. The KPRF also tried to disqualify Vladimir Grudinin, a gubernatorial candidate of “Communists of Russia”, a party widely considered to be a Kremlin project to split the left-wing opposition vote. Grudinin’s name, some argued, was deceptively close to that of Pavel Grudinin, a popular former presidential candidate of the KPRF, and the Communists of Russia is known to have supported similar “doppelgangers” elsewhere. Then, a week before the vote, Sokol withdrew his candidacy, ostensibly due to his hospitalization with peritonitis, which prompted speculations that the Kremlin did not want to face what looked like at best a second-round battle and, at worst, an embarrassing defeat. It will be interesting to see the ruling party’s tactics from here, which could be a mix of focusing on the region’s legislative election to acquire a blocking majority and hoping that LDPR candidate Mikhail Molchanov – who now fashions himself as Konovalov’s main opposition – will manage to draw votes from the governor.

- Observers’ reports: The authorities have not only been restricting independent election observation missions through legislation, but also by the means of intimidation. September saw the arrest of Grigory Melkonyants, co-chair of Golos, as well as searches at various regional Golos affiliates. This betrays nervousness about observers discovering and publicizing evidence of election rigging at a time when the authorities are increasingly relying on oppression, rather than subtler forms of manipulation, and political risks are growing. This also means that the work of observers who, in spite of the risks that they face, continue reporting on violations, is as important as ever.

- Influence of the non-systemic opposition: While many of its representatives have been forced into exile or imprisoned, representatives of the non-systemic opposition have continued to try influencing domestic politics, e.g. by virtually appearing in protests, publishing investigative material or political manifestos, or – in the case of Alexey Navalny’s team – suggesting electoral strategies fit for the new domestic political situation. It will be important to inspect what difference this work, which almost always builds on grassroots work performed in previous years, does to election results in more pluralistic regions.

- Any sign of political machines breaking down: As mentioned above, the past year and a half has put a strain on the understandings underpinning Russia’s domestic political system. For the Kremlin, these elections are not just – and perhaps not even primarily – an act of political theater to legitimize the status quo in the regions, but a stress-test before the upcoming 2024 presidential election, which, from Putin’s point of view, has to be a grand popular acclamation in support of himself and his war. For this, the Kremlin will need to ensure that even with the uncertainties inherent in the evolving new normal, the growing scarcity of funds, stress on the institutions, a massive restructuring of the economy and a redistribution of assets, the people on whom it relies to engineer this acclamation – regional officials, municipal heads, enterprise directors, etc. – will either remain loyal or can be safely disregarded (e.g. in case online voting can be easily manipulated). For this reason, it will be important to watch not only for any signs of strain in these very important relations during the votes, but also for the issues along which local dissatisfaction can meet elite frustration, from local self-governance to development priorities.