The second wave of the pandemic is hitting Russia’s regions harder than the first and most regions are ill-equipped to deal with it. In some, political squabbles impede effective policymaking; these conflicts also highlight why the Kremlin’s model of governing the regions falls short of expectations in crises.

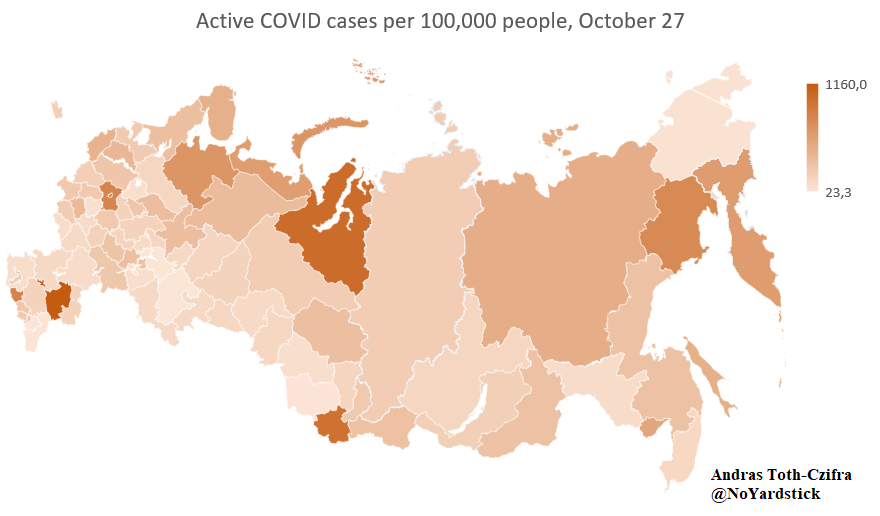

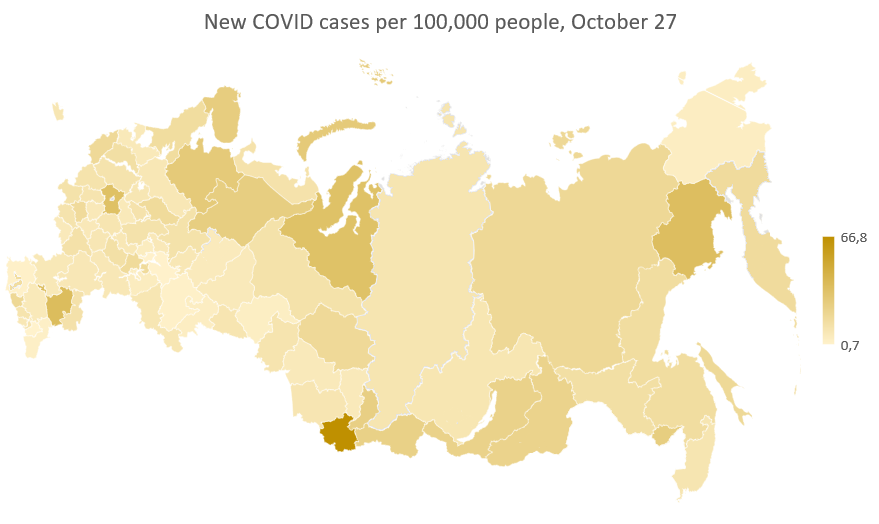

Russia is deep in the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and while Moscow still registers the highest number of cases among the country’s 83 federal subjects, the second wave seems to be hitting regions harder than the first one did. There are significant doubts about the accuracy of the official data – one former Rosstat researcher thinks that the real number of deaths could be as large as three times the official count – but even based on official figures some regions seem to be on a dangerous trajectory. As of Tuesday, 27 October, Moscow only had the fifth highest number of active COVID cases per capita (806). The situation was more severe in the North Caucasian republic of Karachay-Cherkesia, the far-eastern Altai Republic, the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District (YaNAO), a northern oil- and gas-producing region, and the Republic of Kalmykia, a small, mostly Buddhist region on the Caspian coast where this figure was a whopping 1160, almost ten times as many as in the neighbouring, densely populated Rostov Region, which also experienced a bad outbreak this autumn, resulting in the resignation of its minister of health. Unsurprisingly, Moscow, the Republic of Altai, Kalmykia and the YaNAO (along with the remote Magadan Region on the coast of the Okhotsk Sea) were also among the five regions adding new cases at the fastest pace.

The situation in many regions is dire. There is a lack of equipment – CT and ventilators in particular – and increasingly a lack of doctors, either because doctors and nurses are themselves falling ill or because a lot of them have left to Moscow where salaries are much higher. The pandemic has reached smaller towns and settlements where health care facilities are even more run-down and remote than in bigger cities. Most regions are also fiscally unequipped for the second wave.

Khural and Kurultay

Kalmykia and the Altai Republic have also recently experienced political turbulence, more precisely, local elites have risen up against Kremlin-appointed “varangians”: governors nominated by Moscow, without strong links to local power groups (often, though not in these two cases, without any roots in the region they were appointed to lead). In September one-third of the deputies in El Kurultay, the legislative assembly of the Altai Republic, put a motion of no confidence against Oleg Khorokhordin, the governor, on the agenda. At the same time, several deputies in Kalmykia’s parliament, the Khural, including senior lawmakers from United Russia, demanded the resignation of Batu Khasikov, the head of the region. It appears that Khasikov, a former kickboxing world champion, started to replace people appointed by (and often related to) the republic’s former head, Alexey Orlov, too fast and with too much enthusiasm (even as he supported Orlov’s appointment to the Federation Council). One of these people happened to be Saglar Bakirova, the head of United Russia’s group in the local parliament, whose husband is related to Orlov. Khasikov faced criticism from the public too, mostly for following orders from Moscow: both the decision to nominate Orlov to the Federation Council and the decision to appoint a former head of the separatist Donetsk People’s Republic to head Elista, Kalmykia’s capital, in 2018, triggered protests.

Kalmykian deputies even sent a letter to Vladimir Putin to complain about Khasikov’s failures that included the region’s inability to deal with its COVID outbreak, but not only. Kalmykia, a mostly agricultural region, is also struggling with devastating drought and the government, according to the deputies attacking Khasikov, acted too late.

In the end, both parliaments have put off holding the vote of no confidence. For now. But this required, in both regions, United Russia scrambling to prevent the embarrassment of the local legislature voting the president’s appointee out of office.

Contradictions

In the report of the BBC’s Russian-language service about the situation in Kalmykia, there are several telling details that reveal how the highly centralized model of governance that the Russian government developed in the past two decades, and that in the past years have come increasingly to rely on the appointment of technocratic outsiders to manage regions and keep local elites on their toes, is uniquely incapable of dealing with cascading crises like the ones this year has brought, but often even to resolve differences that block effective political decision-making.

Kalmykia had to turn to the federal Ministry of Agriculture for funds to execute drought relief. Like most Russian regions, due to the gradual centralization of revenues, Kalmykia is in no position to finance such a policy itself. In fact, just so that farmers can feed animals in the winter months the republic will need 1.87 billion rubles, about one fourth of the government’s own revenues (and more than 11 percent of its 2020 budget). The situation would perhaps be slightly better now, had the region’s government acted earlier. But the local ministry of agriculture hesitated – according to a local United Russia deputy the reason was perhaps that this would have weakened Khasikov’s positions in the capital.

In this mess, both sides were looking to Moscow for help and for policy solutions. Both Khasikov and the deputies opposing him went out of their way to signal to Putin that they were on his side but their opponents were not. In September, only following a desperate plea by Alexander Boltyrov, a member of Kalmykia’s Public Chamber, to the region’s Duma deputy, did the federal Ministry of Health sent a delegation to the region (the Ministry of Agriculture later did the same). The situation seems to be better, but it is far from resolved. And while United Russia is busy putting out fires, the next crisis is always on the horizon, be it a massive dying of fish in the republic’s biggest reservoir or falling revenues.

Problems are similar in the Altai Republic, where Russia’s health watchdog warned of an “Italian scenario”, an explosion of the pandemic, the governor requested further personnel – even students – to help with handling the caseload, and epidemiologists advocated a hard lockdown, which, knowing Putin’s position on the issue, presently no governor would risk to suggest, especially not one whose position is hanging by a thread.

Aside from the contradictions between the Kremlin’s preferred model of governance and the requirements of effective policymaking, both cases also highlight Moscow’s smouldering fear of separatism, which was reflected in this year’s constitutional reform. Both Kalmykia and the Altai Republic are “regions with an ethnic character” (although with a Russian majority population in the Altai Republic) where if they want to, local elites can stir up cultural sensibilities in addition to the usual grievances. And as several recent examples have shown, regional elites are increasingly willing to side with disgruntled voters if their interests so demand.