The year 2023 will be bumpier for many Russian regions than the past year was. Warning signs are already visible: tighter money, distracted officials, more friction points. The September regional and local elections are not without risks, either.

Elections still matter

We are eight months away from this year’s “single day of voting” – when Russia holds elections on various levels in several regions at once – but from the number mentions of the votes in various contexts by Russian officials and politicians in recent weeks you could think that the elections are right around the corner.

There sure are a large number of votes planned. Twenty Russian regions will hold gubernatorial elections – this includes a mayoral election in Moscow – and sixteen will hold regional legislative votes – at least, barring a “gubernatoropad” in the spring when Putin usually fires unpopular governors. In Moscow and the Moscow Region mayor Sergey Sobyanin and governor Andrey Vorobyov will both stand as candidates after a decade in office. Elections will be held in some of the regions hit hardest by sanctions in 2022, such as the coal producing Kemerovo and Khakassia or the Samara Region that relies on carmaking. Putin has already started meeting the leaders of other regions facing various elections in September, e.g. Novosibirsk governor Andrey Travnikov and the head of Bashkortostan Radiy Khabirov. The question, as always, is: do these elections matter at all?

At the first sight, the contrast with the 2018 votes – for many regions in question, the previous elections – could not be starker. Then a combination of a wave of discontent over a disputed pension reform and falling living standards, dismay over Moscow’s inattention to local problems and grassroots opposition activity resulted in four unexpected electoral upsets for Kremlin candidates (although one of these votes were then rerun with different candidates). Out of the three eventual “systemic” opposition candidates who won, only one remains in office today: the communist Valentin Konovalov in Khakassia. Sergey Furgal who won in Khabarovsk was famously arrested and jailed in 2020, although his trial only started in mid-2022. Vladimir Sipyagin who won in the Vladimir Region was offered an easier way out: he took up a mandate in the Duma after the 2021 election.

There have not been any second-round battles, let alone surprise upsets in gubernatorial elections since, and it would be very surprising if we saw one this year. Only a small handful of regions that hold votes in September have even remotely recognizable “opposition” politicians, e.g. Omsk where two communist candidates supported by Alexey Navalny’s “Smart Voting” managed to defeat United Russia politicians in the 2021 Duma election.

Even more importantly, it is unclear what systemic opposition parties are even allowed to stand for in the current environment. One of the few clear narratives coming out of the Kremlin over the past year is that of consolidation around the domestic political leadership in what is increasingly depicted as a defensive war – so much that the Kremlin is reportedly planning to contest the elections with the slogan of “unity” – which currently leaves fewer opportunities for these parties to tap into even local discontent, and may make regional elites who have traditionally relied on regional party organizations to get into local legislatures more careful. The Communist Party’s nascent activist base has been all but gutted, with only a handful of personalities still standing in regions with comparatively more open and pluralistic political environments.

Public administration reforms introduced in 2021 already pointed towards a more direct top-down control over regional politics vis-à-vis regional elites, and the context of the war seems to have supercharged this process – at least temporarily. It is worth remembering that last year the center seemingly also had to make concessions to regional elites, e.g. through offering to loosen the rules requiring them to report their wealth. Furthermore, to stress once again, politics is not equally tightly controlled in all regions and conditions can change fairly quickly over the next eight months. Nonetheless, seen from January 2023 it looks like the authorities will have to deal with only sporadic cases of meaningful opposition activity in the autumn.

This does not mean that there are no risks that concern the Kremlin. From this point of view, one of the most interesting developments over the past weeks was the apparent interest in fielding returning troops as candidates in the September elections. Vedomosti reported that several parties, including United Russia and the Communists were planning to do this, while Far Eastern United Russia deputy Andrey Gurulyov, a critic of the current Defense Ministry leadership, went even farther and suggested that Wagner Group veterans should be fielded as candidates as well.

These suggestions raise several questions. For one, as the independent election observers of Golos highlighted, Wagner veterans who had been recruited from prisons and had previously had their passive electoral rights removed, are unlikely to see these restored any time soon, even with a presidential pardon. But the fact that there seems to be a sudden interest in this across the political elite also prompts the question of what the purpose of it might be. This could be a genuine way of trying to integrate veterans into a pro-Kremlin political community, lest they become a social and political risk. But it can also be a way for the authorities to put a positive spin on the war, an issue that cannot be simply ignored in the campaigns, not even to the extent that it was last year. In this case we can expect to see some high-profile people for United Russia to showcase as candidates (in the same way as doctors and civil society personalities were in 2021), but nothing more. And, last but not least, this can also just be a way for the Kremlin to measure the popularity of the idea.

After all, if it is true, as several reports on the state of the federal political elite suggest, that there is no discernible “peace party”, but there is a growing rift between pro-war factions, then that is where a challenge to the leader can come from. In this case it would make perfect sense from Putin’s point of view to show that war veterans – the Russian citizens most affected by his disastrous and mishandled invasions – are standing gwith him. In the same way as postponing or scrapping regional elections would likely suggest weakness, so too would ignoring this growing constituency.

This is why it is going to be interesting to see how United Russia’s primaries – votes usually held in the spring to appoint candidates for autumn elections – turn out this year. Not to say that these votes are in any way representative or democratic, of course – in most cases they are not – but the past years have seen some genuine competition in certain regions. And even if the authorities unduly influence the vote (as they most likely will be), they can still use it to measure the popularity of the idea further, if they want to.

Fiscal inertia

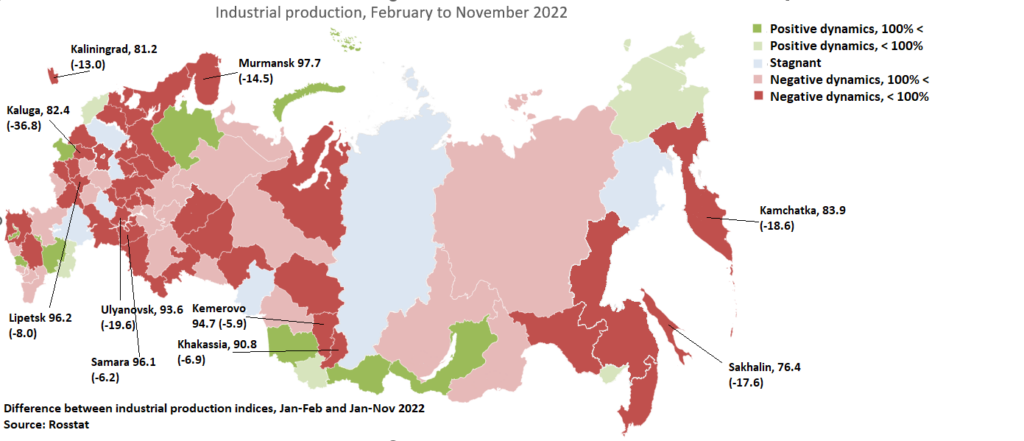

In 2022 Russia’s self-induced economic crisis did not affect all of its regions equally: industrial decline was the most pronounced in regions relying on industries with complex supply chains, e.g. machine building and carmaking, as well as on industries that lost export markets (timber, coal, metallurgy). The decline of retail trade, another indicator signaling trouble, was the most visible in bigger cities. Still, due to the first half of the year (and due to increased federal transfers), regional budgets on the whole seem to have closed 2022 with a surplus, unlike the federal budget. The yearly data, however, masks a downturn that started over the summer. This is when the commodities bonanza that regions enjoyed in the first half of the year ended, export markets disappeared and long-term losses and significant upfront costs associated with a permanent economic rupture, which seemed to be avoidable until then, became unavoidable.

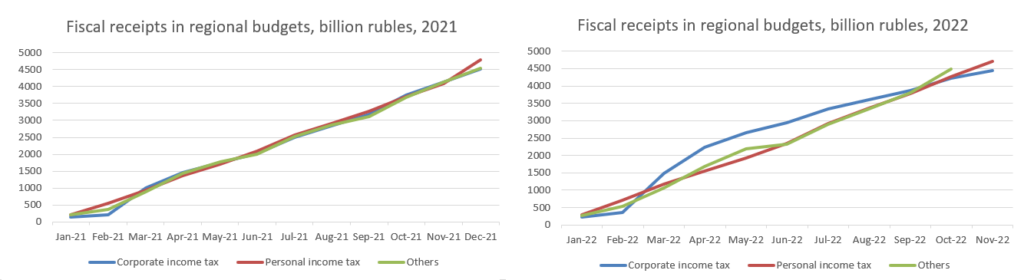

This rupture is the very visible when it comes to corporate income tax receipts. This is due both to bumper revenues realized by some regions in the first half of the year (typically those where energy and commodities companies are headquartered), and a rapid fall of profits afterwards. Monthly figures published by the Finance Ministry show these dynamics pretty well (especially when comparing them with 2021 records). In particular, regions relying on coal (Kemerovo, Khakassia) and metallurgy (Belgorod, Lipetsk) collected the overwhelming majority of their corporate income taxes in the first half of the year, and suffered a slowdown later. As a result, in the end of November 2022, corporate income tax receipts on the whole were only 12 percent higher than a year ago, roughly equal to yearly inflation in that month. Personal income tax receipts, another important revenue for regional budgets, were up by over 15 percent – which seems more stable, but this is partly the consequence of the indexation of public sector salaries (including the military).

Source: MinFin, 2023

Corporate income tax receipts are going to sag in the foreseeable future. Apart from the direct and indirect effects of the oil price cap, the planned oil product price cap and the lost energy export markets on these industries (and as a consequence, downstream industries). Export-oriented industries are also suffering from transit bottlenecks. A potential second round of mobilization and the obligation for enterprises to take part in the reconstruction of the occupied territories are de facto taxes on the private sector, further decreasing profit margins and productive investments (not to mention tariff hikes and increased pressure to invest in certain regions and sectors).

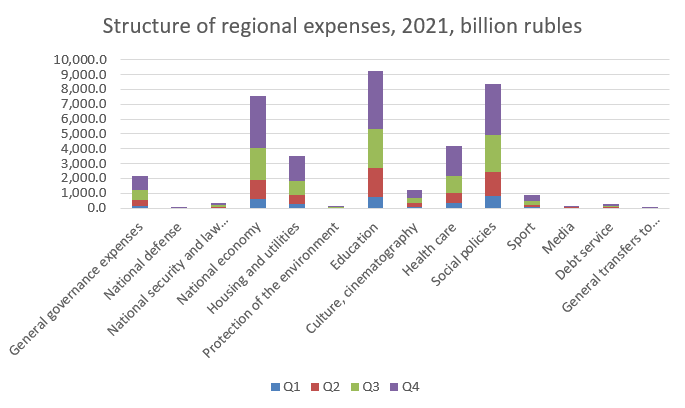

Dependence on the state as regards budgetary transfers and capital investments is increasing. The problem is that while the state has clear priorities, it has many, and with a volatile oil and gas price, its fiscal outlooks may be even more unstable than regions’. Pressure points at various points of the budgetary system multiply. So far none of these has caused a serious problem, and barring a very significant loss of oil and gas revenues (which is a possibility), between regional reserves, the National Welfare Fund and bond purchases encouraged by the Central Bank, the budgetary system has enough reserves to survive 2023. Nonetheless, even in this case, these pressure points all represent added political risks. Hospitals reportedly have to cut purchases of medication. Road construction funds are reduced. Regions need to cut expenses to pay benefits to the families of mobilized men.

Source: MinFin, 2022

It is in this increasingly uncertain environment that regional governments are expected to juggle a growing array of potentially conflicting priorities – keeping an eye on prices, on the availability of products, propping up local factories, if needed, spending on the reconstruction of the occupied territories, participate in parallel imports, prioritize military production and mobilization – with little or no clear direction (which itself is a feature, not a bug, of the system). And dozens of them will also face elections in the autumn.

In Russia’s increasingly centralized and rigid fiscal system, where over the past years the relative weight of budgetary grants, which regions may use as they want, has decreased in favor of subsidies and specialized loans that come with strings attached, this is a recipe for problems. Some regions are already making proposals to increase their fiscal maneuvering space. The head of the Chelyabinsk Region, Alexei Teksler suggested at the end of December at a meeting of the State Council, one of the main forums for regions to voice their concerns, that regional governments should be able to write off budgetary loans in the amount spent on tasks related to the war. This would be similar to an actual 2022 measure that allowed regions to use funds released as a result of restructured budgetary loans to mitigate the impact of sanctions. Another potential measure, discussed in the legislature would allow regional budgets to count excess corporate income tax receipts as pre-payment, instead of returning them to companies – another short-termist proposal aiming to reduce the chances of temporary shortages in regional budgets.

The risk of distractions

The federal government has set up a whole series of overlapping institutions to ensure that the needs of the military are met, from channeling production and labor in the necessary direction, to providing more mobiks, if needed. Putin’s public dressing down of Industry Minister Denis Manturov could very likely result in officials proactively trying to prioritize the military industry. A second round of mobilization may be around the corner, which, again, will likely be entrusted to governors. But all this effectively means withdrawing capacity from other policy fields. And while the quality of governance in the regions has undoubtedly grown in recent years, the system, as I have laid out earlier, was not built to handle crises on this scale.

The attitude of the Russian public vis-à-vis the war is notoriously difficult to read – however, as of January 2023 it seems that the war and the losses associated with it – be it dead soldiers or falling standards of living – are not yet enough to trigger protests, considering the state’s current capacity of repression and intimidation and the very gradual downwards slide of socioeconomic indicators.

However, there is ample evidence to suggest that Russian citizens are just as sensitive as anyone else to sudden negative changes in their immediate conditions and will take to the streets, if needed, as, for instance, Dagestani residents did in January to protest disruptions in electricity and gas services, or as conservationist protesters have done over and over again across the country in recent years, even after the state increased repression in 2022. This also adds to the risks of the war eating up governing capacity: as officials are distracted, money is short and responsibility is pushed down the vertical, the chances of fateful mistakes and oversights will grow.

To appreciate what such mistakes can snowball into, consider, once again, the previous election in the Maritime Territory, the one in 2018. In the second round, as the votes were tallied, it emerged that the communist candidate might very well defeat the region’s governor whom Putin had personally endorsed. Unwilling to upset the boss, but seemingly untrained in the subtle ways of plausible electoral manipulation, the local electoral committee waited until almost all votes were counted before it suddenly froze the tally on its website. When it finally updated, the results had miraculously turned around. This was too suspicious even for Russia’s famously supple Central Electoral Committee, which annulled the election. The Primorye vote, along with the three other electoral upsets of United Russia, inspired Navalny’s Smart Voting.

Elections have become much more tightly controlled in Russia since. But between returning troops and distracted officials, political risks will find a way.